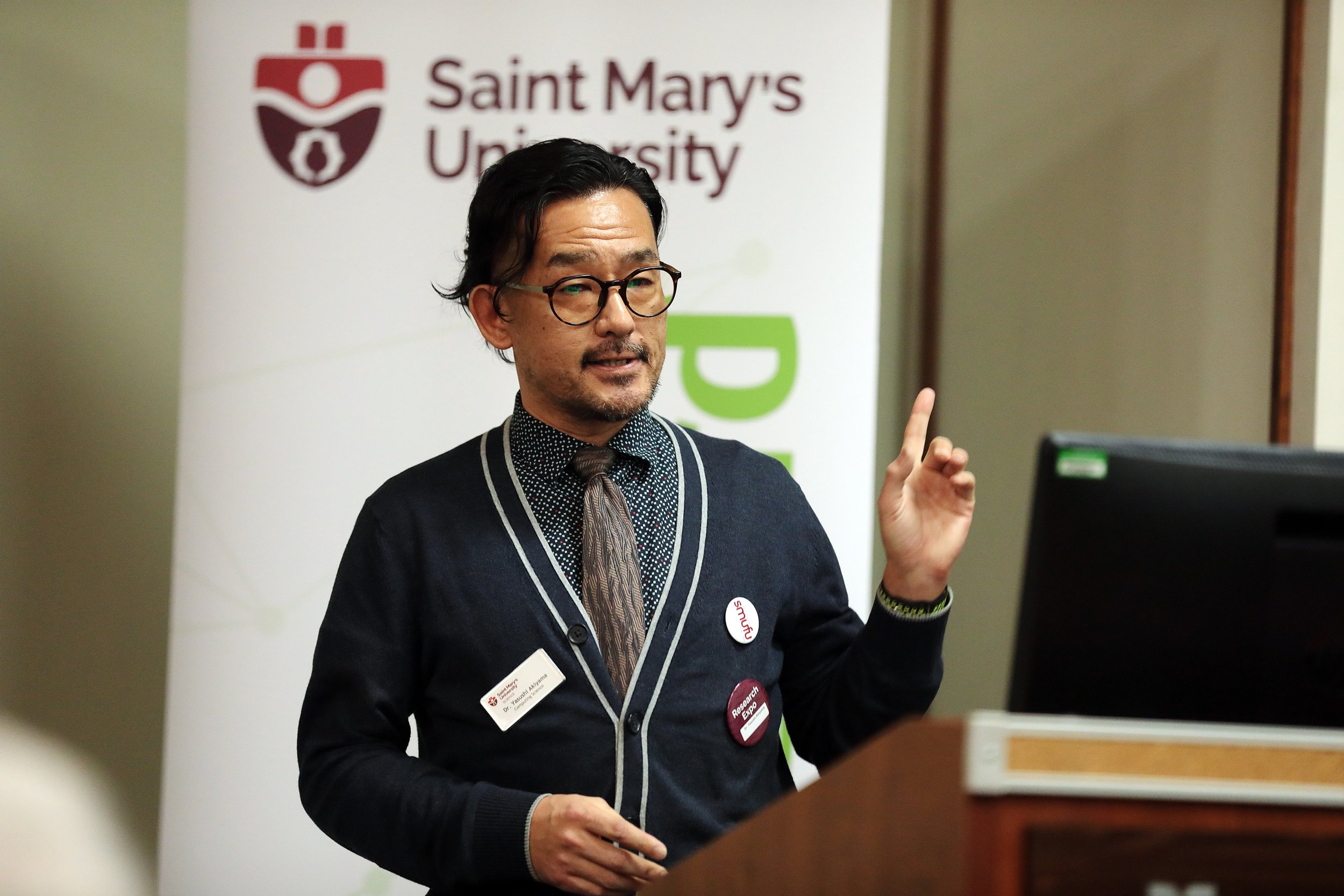

Article by SMU Professor Dr. Yigit Aydede, published in Scientific Reports, examines virus spread in Nova Scotia

Dr. Yigit Aydede

Understanding how influenza and other viruses such as COVID-19 migrate from one community to the next is key to predicting where disease will spread and determining how to curtail its progress. A new article by Saint Mary’s University’s Dr. Yigit Aydede, and Jan Ditzen, Free University of Bolzano, Italy, published in Scientific Reports unveils a new methodology, one that may assist health officials to both predict where viruses will spread and target interventions to halt them.

“The COVID-19 pandemic put mapping at the forefront of both the general public’s and public health experts’ tracking of the outbreak. Dr. Aydede’s research demonstrates the essential role of spatial and temporal analysis when tracking and predicting outbreaks between and within communities.”

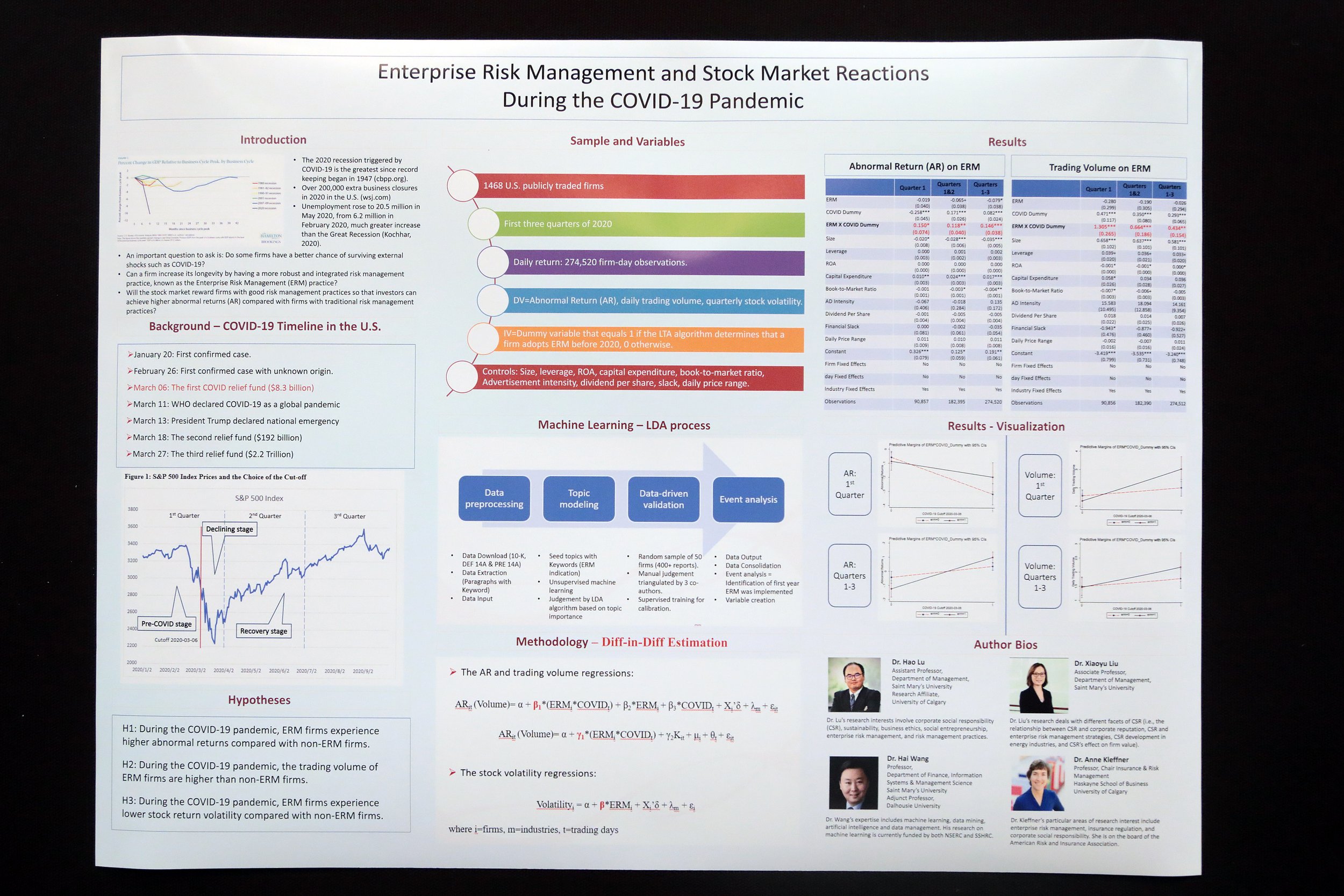

The study, Identifying the regional drivers of influenza-like illness in Nova Scotia, Canada, with dominance analysis - Scientific Reports, is hailed by the journal’s editors as the first epidemiological study of its kind because it combines data concerning geographical or spatial spread with temporal spread (incidents over time), as opposed to more common epidemiological studies which examine temporal spread alone.

The research was only possible due to a unique set of circumstances: unparalleled access to unique provincial healthcare data, new methodology, and the use of machine learning.

“Research Nova Scotia was proud to support Dr. Aydede’s work through the Nova Scotia COVID-19 Health Research Coalition,” says Stefan Leslie, CEO of Research Nova Scotia. “Better understanding relationships between viral transmission rates, air quality, and social mobility will help inform public health decision making, optimize allocation of healthcare resources, and ultimately benefit Nova Scotians.”

The ideal circumstances for data collection arose in Nova Scotia during the first four months of the COVID-19 pandemic. From March to July 2020, health officials asked Nova Scotians to report their symptoms to the province’s 811 telehealth system, where nurses painstakingly recorded and referred citizens reporting a minimum of four influenza-like symptoms. When the data was made available to researchers at Saint Mary’s University, they realized it was exceptional. Far more detailed than COVID-19 PCR tests which only confirm the presence or absence of disease, the symptom data from the 811 records reveals how viruses, in real-time, spread across Nova Scotia’s neighbourhoods and communities.

“This type of data that records symptoms as they arose, early in the pandemic, simply does not exist anywhere else in the world and is due to decisions taken by provincial health authorities that turned the Province of Nova Scotia, in effect, into a living laboratory,” says Dr. Aydede, Sobey Professorship in Economics and the study’s principal investigator.

Dr. Mat Novak, Dr. Yigit Aydede and student, Kyle Morton BComm’23

The inability of scientists and health officials to predict where COVID-19 would strike was a key feature of the disease, one that remained a constant source of frustration throughout the pandemic. “We could watch the overall trajectory of the disease as the number of incidents rose and fell, and we understood the R factor (degree of virulence) but there was no ability to predict the spread of the disease on the ground,” says Dr. Aydede. “Thanks to the Nova Scotia COVID-19 Research Coalition and a grant from Research Nova Scotia we had an unbelievable data set that allowed us to look back at what occurred and identify the communities or locations that were driving the spread in Nova Scotia and further identify key socio-economic factors as well.”

Dr. Aydede adapted algorithms recently developed for the finance industry to analyse economic ‘shock waves.’ “It is not always clear which features or factors are essential and which ones can be dropped without compromising predictive or statistical power,” says Dr. Aydede. “Machine learning, particularly Tree-based methods such as the Random Forests algorithm used here, helps identify relevant predictors in large complex data sets with complex variables and factors.”

The study analysed 112 Nova Scotian communities identified by postal codes and found that 18 communities were drivers of viral spread and then analysed 1,400 socio and economic factors, such home mortgage ownership, employment status and use of public transit that all coincided with the spread.

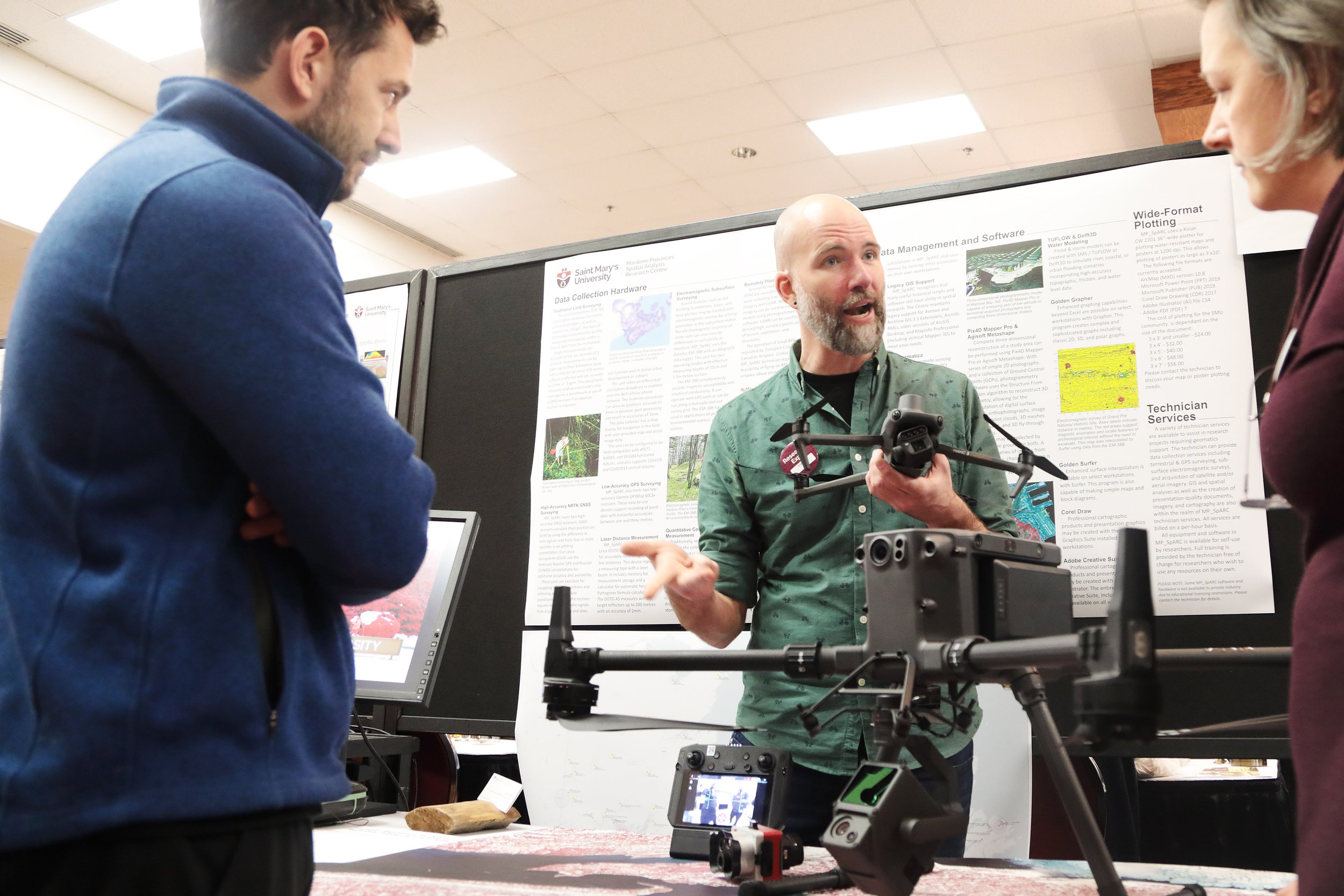

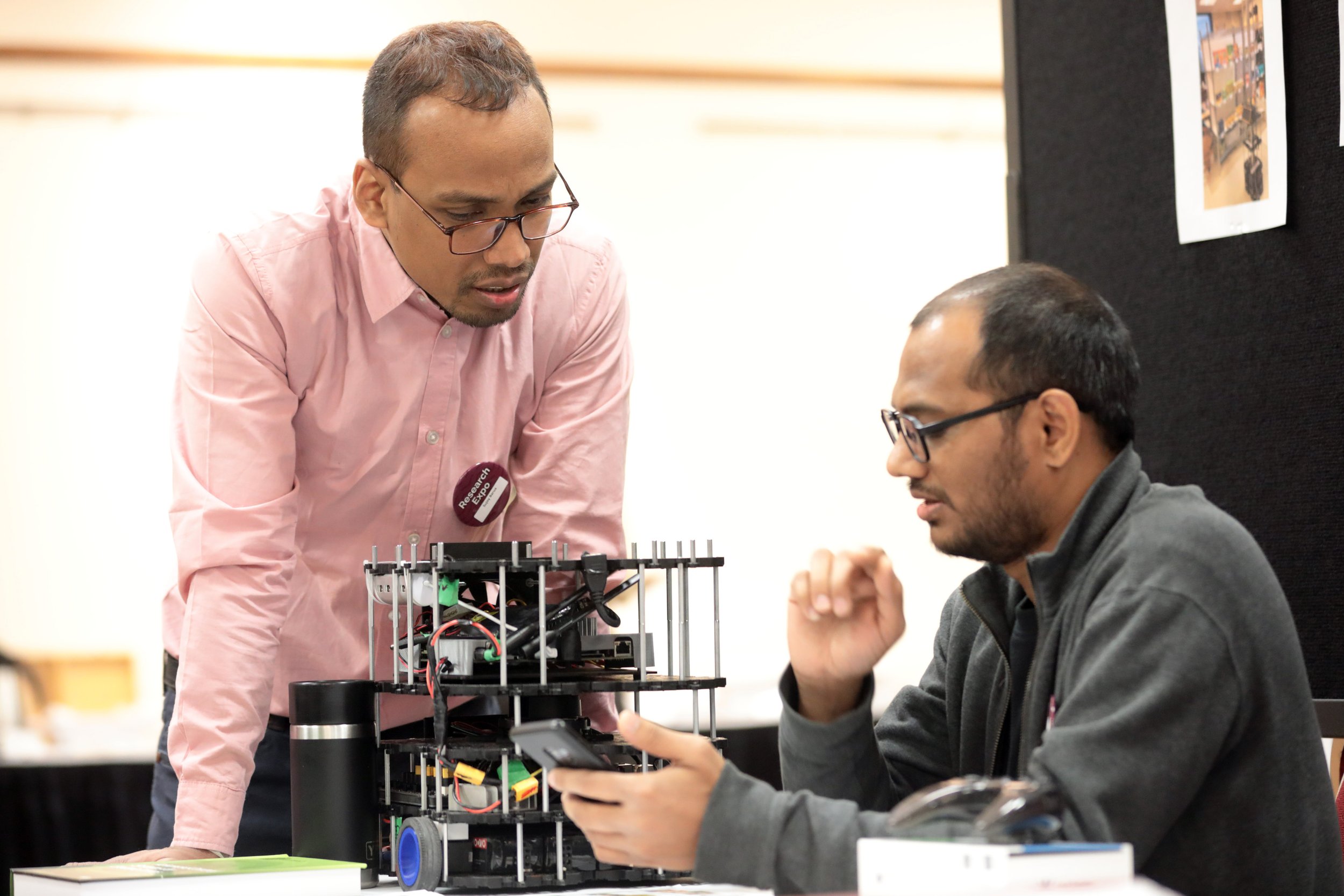

“This important health-related study led by Dr. Aydede is a terrific example of many elements that allow our Saint Mary’s professors to establish research leadership in areas that may seem unexpected for our university,” says Dr. Adam Sarty, Dean of the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research. “By applying methods used in economics to health-related problems and drawing on the expertise of both his international colleagues and the technical data-visualization talents of our multi-disciplinary research lab at Saint Mary’s, Dr. Aydede was able to partner with Research Nova Scotia and the provincial health authority to illustrate the power of such interdisciplinary networking.”

Want to learn more about Machine Learning?

Professor Aydede has just published his book for students of business and social science. Machine Learning Toolbox for Social Scientists | Applied Predictive An (taylorfrancis.com)

About Scientific Reports

Scientific Reports are open-access journals publishing original research from all areas of the natural sciences, psychology, medicine and engineering. It is the fifth most cited journal in the world and its editorial team, in partnership with an extensive network of peer reviewers, provides expert and constructive peer review. Scientific Reports is part of the Nature Portfolio.